Tell us about your art.

Currently, I focus on portraiture and landscape with an affinity for capturing Black women in all their glory, beauty, and vulnerability. Eyes are truly windows to the soul—I pay special attention to them. When you first look at one of my portraits, their gaze will generally be the first thing you see. Bold color, lush floral backgrounds, and all shades of melanin under the sun—from deep purples to charcoal browns, to tan olives and eggshell whites—are present. We are here, we are beautiful, and we have a story to tell.

What's your creative process?

I typically start a painting with a mood board with questions around the landscape and background of the painting and what I want the portrait to say (about myself and what I’m going through in life). After I feel good about the direction the mini mood board is going in I’ll start sketching the piece and getting the canvas ready to prime with a clear gesso.

A painting is finished when it tells me it is. When I think I’m done, I’ll do a “fresh eye” check as my drawing professor says, where I’ll look away from it and see if any part of the painting is screaming at me. If not, and I’m still satisfied, I’ll find a name/title for the work.

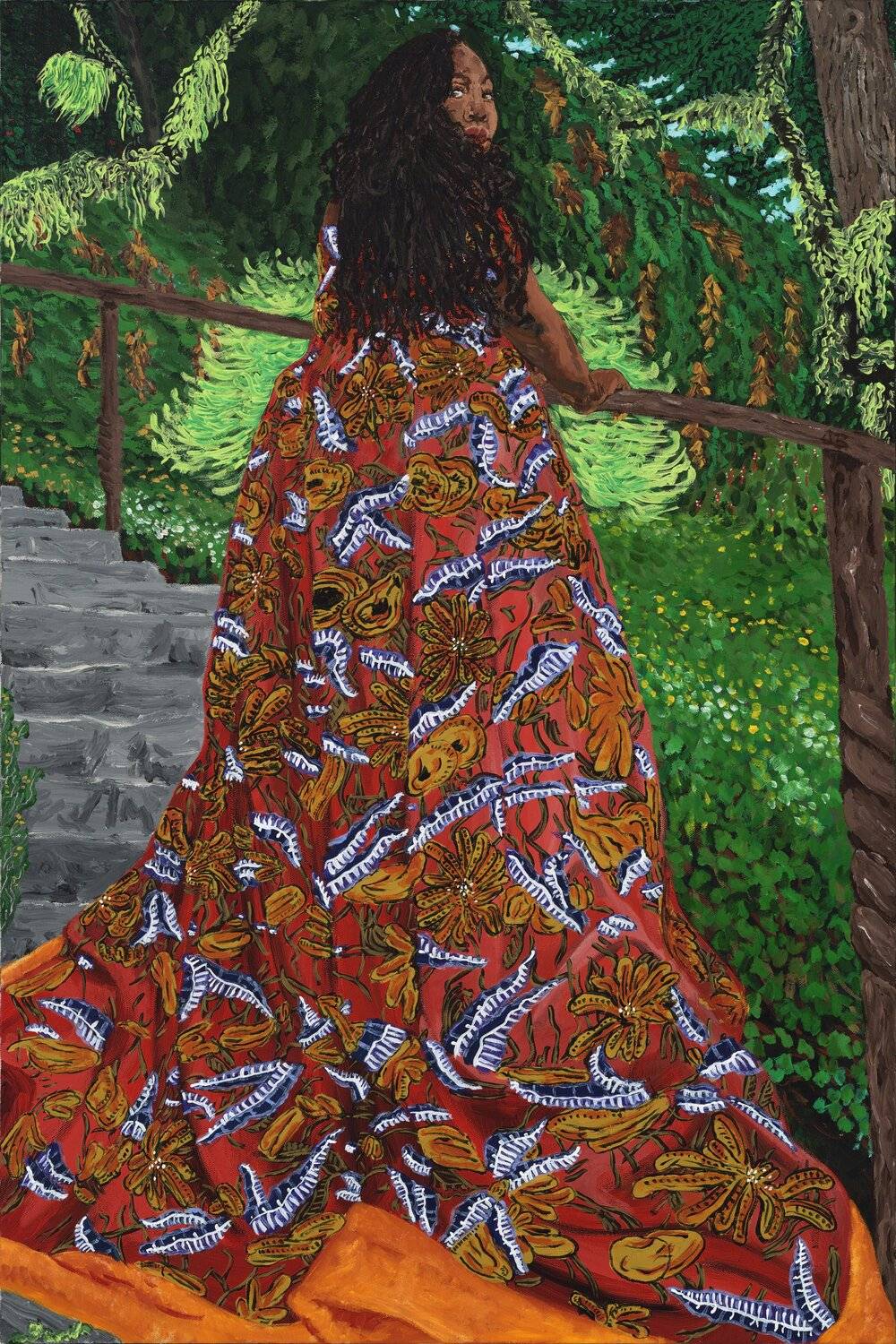

Zanele Mutepfa-Rhone , courtesy Sadé Duboise

Are the women in your paintings with names real people? How do you choose who to paint?

The women in my paintings tend to be a type of fictional self-portrait. When I paint a portrait, there is an internal dialogue or emotion I’m feeling that is represented in the painting through the facial features and expressions. This is generally how I choose which portrait I’m going to paint. After painting it, I mine through what I felt through the session and pick a name that fits the experience. The experience is like naming a child for me. There are some paintings, like Zanele Mutepfa-Rhone, Mic Capes, and Asia Greene-Rhodes that are real people living in the PDX metro. When I paint portraits like this, it’s with the hope they will enter a permanent collection. Zanele is currently at the Portland Building and Asia Green-Rhodes is in the portable works collection of RACC.

Clockwise, from top L: Tsholofelo, Adana, Bolade (honor arrives), Azurae, and Amelia, from Sadé's current practice of painting Black women in the wilderness. Pics courtesy Sadé Duboise.

How did you learn how to paint?

I was self-taught until I recently secured a full-ride scholarship to PNCA. Now I’m working towards my BFA in painting. I'm learning a lot of skills to make my practice more efficient. I still learn a lot about painting from other artists via Instagram, YouTube, and other platforms online. It’s free, and there is so much knowledge out there for the taking.

What does a day in your work life look like?

My studio practice has been hectic lately. In the last 6 months, I’ve worked on various large-scale projects such as a 9 X 12 ft portrait mural of Justice Nelson, the first African American to sit on the Oregon Supreme Court, at the Adrienne C. Nelson High School, the Multnomah County COVID-19 REACH coloring book, and Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art (JSMA) Commission for the BLM exhibition. I was also filmed for an upcoming OPB Oregon Art Beat segment venturing into my studio as an artist and detailing the process of painting the JSMA 7 X 8 ft commission… Lots of Dovetail Workwear clothing was worn during filming!

To grow as an artist within my practice, I applied to the Pacific Northwest College of Art, and am now fulfilling my BFA as a full-ride Equity Scholar. My practice currently is split between 16-week course loads and my personal studio work. A typical work day would be 6 hours of studio for class, predominantly in drawing and painting, and 2 to 4 hours of work on smaller, personal works which I sell on my online shop. When I’m not painting, I take care of the administrative side of my practice by bookkeeping, inventorying materials and supplies, cleaning my personal and school studio spaces, and shipping orders from the online shop.

What did you want to be when you were growing up?

First, a veterinarian because I loved finding stray pets and taking care of them. Then I wanted to be an artist because my father could draw and it was my connection to him when he was in the Navy and moved to Alaska. In high school, I tried to become more practical, and said I wanted to be an artist and civil engineer. I went to OSU with scholarships to pay my way as an engineer, and didn’t get anything for wanting to pursue art, so I went with engineering. I didn’t graduate, and didn’t like the office work. I preferred doing the hard work and heavy lifting, which excited me about Constructing Hope and Steamfitting. I kinda fulfilled my dream by doing both artistic and construction work for a few years in tandem, but overall, I’ve always wanted to be an artist full-time. Now I’m living that dream out every day.

Sadé during her pre-apprenticeship program.

Pic via Constructing Hope

How did you get into the trades?

I decided to leave my lab assistant job to go into the trades for various reasons. I had wanted to go through the Constructing Hope program years prior, but decided against it because I was encouraged to stay the course in college. I was told I would graduate and enjoy an office job, but I’m a very hands-on individual. During my freshman and sophomore years in engineering school at OSU, I found that I enjoyed being outside and physical movement, putting basic math skills to practice in real life, and problem solving. I’d been debating with myself for years about getting into the trades but never did because I was told being an engineer was the way to go to be secure financially—truth is I didn’t much like advanced math and the sciences, and after seeing a day in the life of an engineer, I found that job to be monotonous.

In 2018, I told my husband the trades was something I wanted to do and he supported me—even though our household would be short of my paycheck as I went through the Constructing Hope program. If I didn’t have the support, I don’t know if I’d have followed through. Because I did have that support, I was able to finish the program and get into Local 290 as a steamfitter apprentice. I increased my pay, had full medical, pension, etc. By getting involved in the trades, I was able to pay off all my consumer debt, student loans, and put money down for a house in two years (about $32K for debt/loans/down payment, as my husband paid our monthly expenses). If I had stayed in an office job, I would have been bored to tears, and not have gotten financially stable as fast as I did with my trade experience.

I also did it as an example for my younger siblings. Growing up as the oldest sibling of four in a single-parent household, I was told the only way to change my income status was to go to college after high school. That was “the only way,” and you had to either be an engineer, nurse, doctor, etc. By going into the trades, I hoped to show my siblings that there were other options to become financially independent… Which worked! My sister Tatyana Smith decided to go into the Constructing Hope program, graduated, and followed in my footsteps with becoming a steamfitter at Local 290. She’s gone farther than me in the program, enjoying her work and financial stability and I’m super proud of her.

Sadé in Dovetail's Spring 22 Hemp utility crop + Solid tank

What made you become an artist?

I started painting seriously in April 2017. Before then, I’d partake in painting every now and then, and not for money. For 4 years, I practiced art outside of my work at Multnomah County, OHSU, the Constructing Hope program, and a steamfitting apprentice out of Local 290. In January 2021, I decided to start the year fresh and go into my art practice full-time, and I’m happy I did. It gave me the freedom and time to put all my energy into building my practice, obtaining awesome commissions, and running an online store more efficiently. Another candid conversation with my husband made me start practicing art full-time. He saw the enjoyment I got in my artistry, and said I could leave my job and paint, even if I didn’t make any money. Thankfully, that isn’t the case—within the first year, I’ve made more than I did while working a traditional job. My practice isn’t focused around making a lot of money, however—more about freedom, creativity, rest, and balance. This year, my husband and I are family planning. This practice gives me the ability to build a family without the pressures of a traditional job.

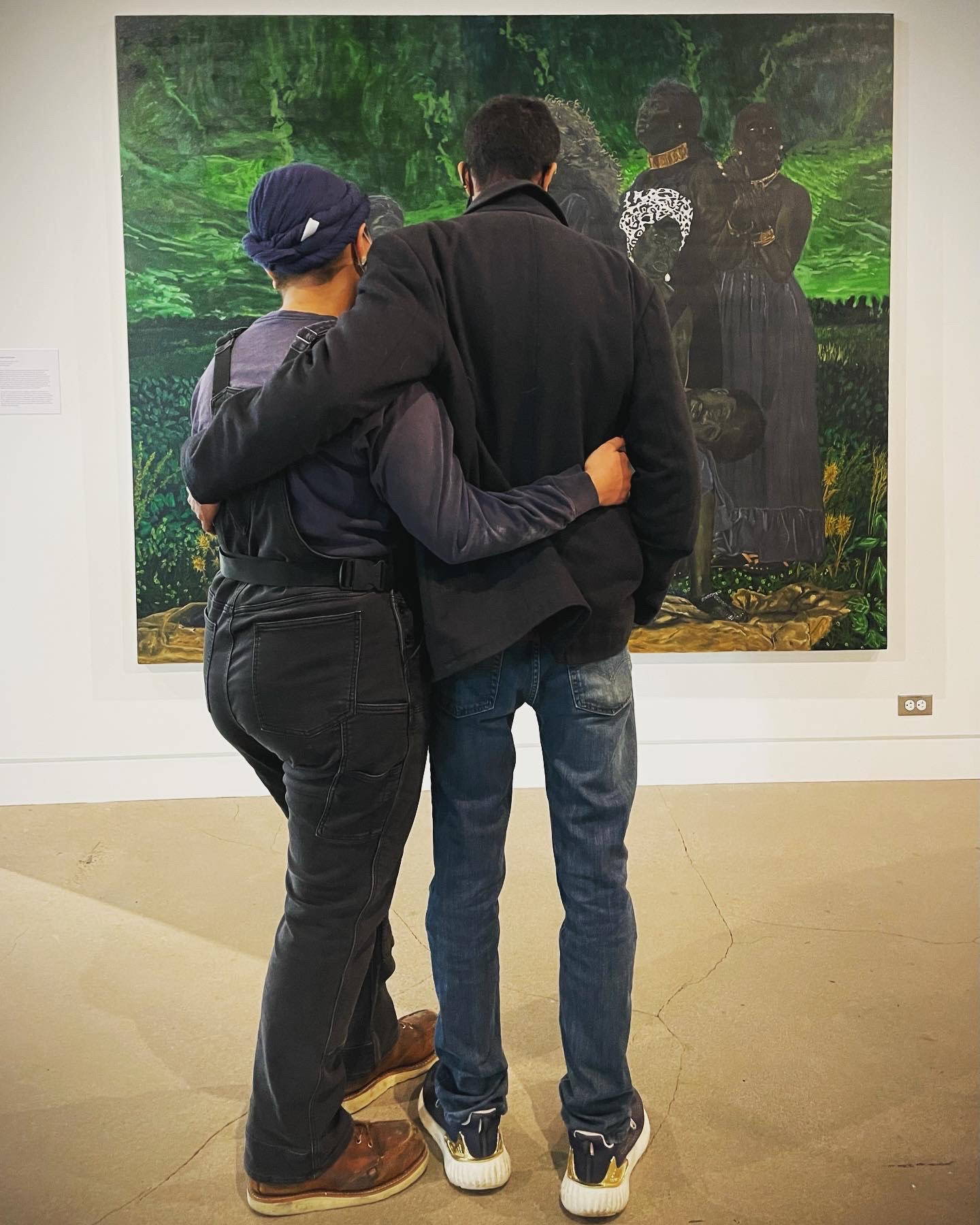

Sadé and her husband look at her painting for the JSMA exhibition.

How does your work in the trades impact your new career in the arts?

My pre-apprenticeship and steamfitter experiences exposed me to all the construction going on in the PDX metro area. It’s amazing how much work is being done. With that, I realized that all these public buildings would need art. That opened up my eyes to the Regional Arts and Cultural Center and the need for artwork in these public spaces. I realized I could contribute myself and artwork in this way.

Tell us something dirty.

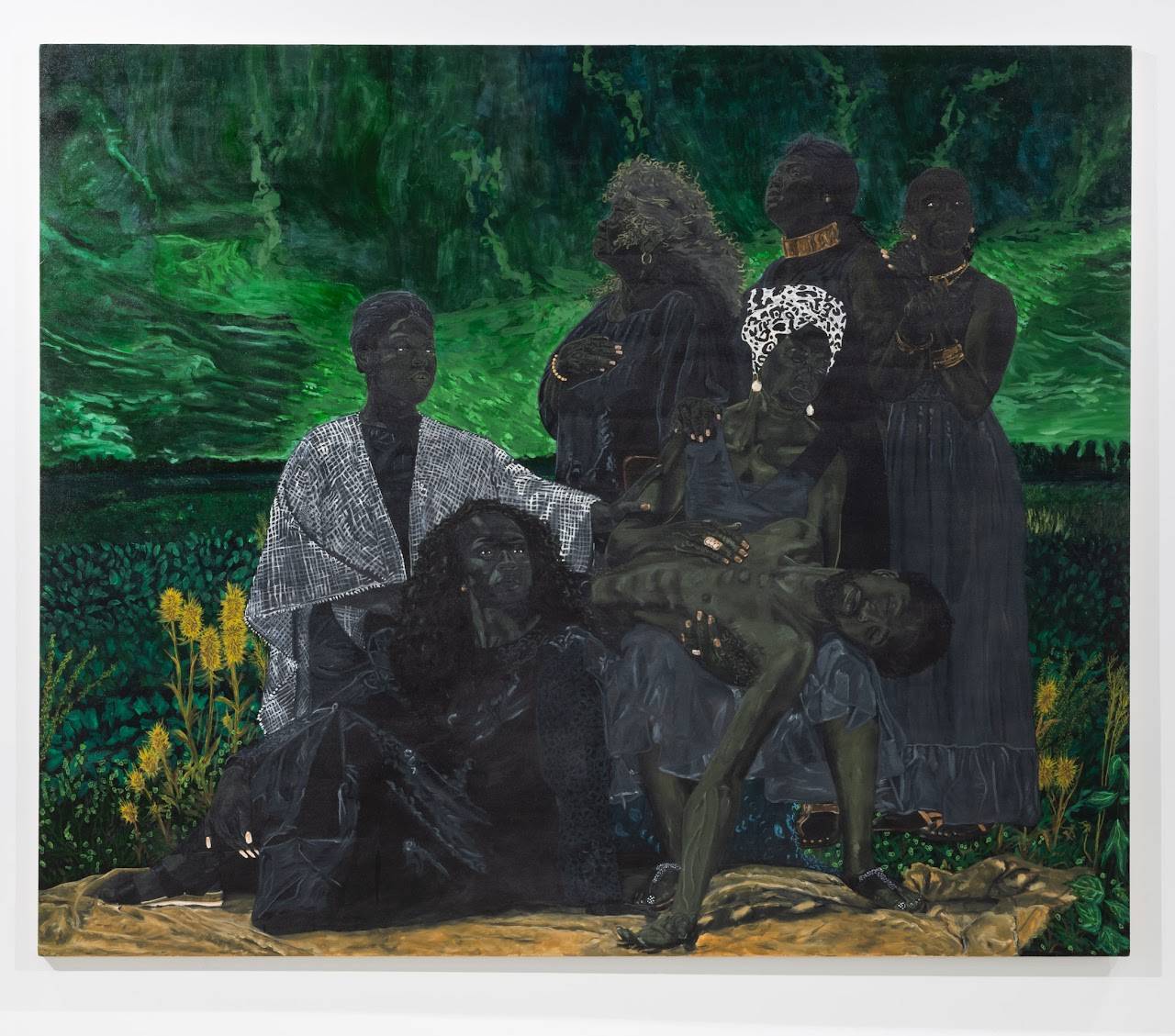

Not necessarily nasty, but I was finishing the 7 X 8 ft commission for the JSMA exhibition. I had two weeks to finish the painting and spent the last two days pulling all-nighters. I had never completed a piece that big before, so I had an unrealistic expectation of how much time it would take me. I was sleep deprived, and jacked on candy and bowls of ice cream, trying to stay up without any self care (shower, teeth brushed, exercise, healthy eating, etc.) I was so stressed and ready to be done with the work. After I dropped the piece off at the museum, I slept pretty much 4 days straight.

Well worth the all-nighters: Sadé’s 7 X 8 ft commission for the JSMA exhibition, The Collective Mourn. Image credit: Mario Galluci, courtesy of the Artist and Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at PSU

Check out Sadé's art on Instagram.

Sadé's pronouns are she/her/hers.